For the first time since their introduction in 1999, Farm Management Deposits have topped $6 billion. Khan Horne, General Manager of NAB Agribusiness, explains which sectors and states have fuelled this incredible growth, and what the result means for the Australian agricultural sector.

It’s hard to overstate just what a golden age Australian agriculture is enjoying, and nowhere is this clearer than in the incredible growth story of Farm Management Deposits.

Introduced in 1999 by the Federal Government, Farm Management Deposits (FMDs) are a form of cash flow management, whereby farmers can put away money in the good years as a buffer to protect themselves in the lean years. FMDs followed government trials of other cash flow management models, such as drought bonds and the income equalisation deposit scheme.

It’s been a slow build but in recent years there has been spectacular growth in both the number of FMDs and the amount of money deposited in them. On the latest available 2017 figures, Australia now has 54,383 FMDs collectively containing $6.09 billion – an incredible growth story considering that just three years ago the figure stood at $4 billion. There are now four states (NSW, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia) that each have over $1 billion in their FMDs, and Western Australia, with deposits of $917.5 million, is close.

That is phenomenal growth in the amount of money that Australia’s farmers have saved in tax-effective accounts.

In 2016-17, two factors led to this spectacular growth. The first was the rule change that saw the limit on FMD deposits increase from $400,000 to $800,000. This coincided with farmers enjoying once-in-a-generation favourable economic conditions combined with good seasons across the board.

What’s the ROI on an FMD?

Australian farming conditions are characterised by large variances in seasonal conditions from one year to the next. FMDs allow them to defer income from the good years. That means they lower their income and the amount of tax they pay during the boom times. That money can then be withdrawn in the tough times when their income is low or non-existent and they don’t need to worry about falling into higher tax brackets.

A recent example of that process playing out is the dairy industry in Victoria. In 2015, the Victorian dairy industry accounted for 2511 FMDs that contained $215 million. By 2017, according to the Department of Agriculture & Water Resources, that number had dropped to 2023 FMDs containing $186 million. At a time when factors including drought, contracting international demand and falling domestic milk prices were impacting Australia’s dairy farmers, a significant proportion of them could fall back on their FMDs. They could arrange a cash injection to their business, making sure they wouldn’t have problems, for example, paying creditors and staff.

There are other worthwhile things farmers can do with spare money, such as putting it into super, pre-pay inputs or buying equipment. But the farmers with FMDs I speak to say it’s a reassuring feeling knowing they have a resource to call upon when they get hit with lower prices, lower yields or both at the same time.

A handy metric

FMDs aren’t a perfect gauge of the health of various industries and regions within Australia’s agricultural sector. By definition, they’re only used by farmers doing well enough to have money to put aside. On my rough arithmetic, only around a third of farmers are using them, even given the recent surge in their uptake. That noted, they do provide a valuable insight into which industries and states are doing better than others.

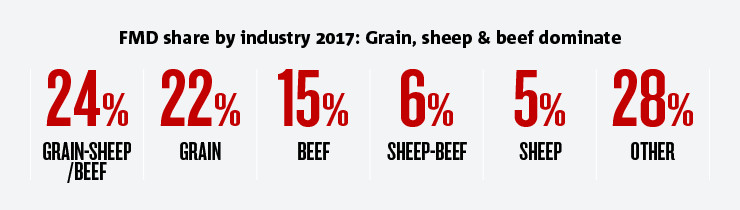

For example, the chart below indicates what a good time it is to be farming beef, sheep and grain.

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

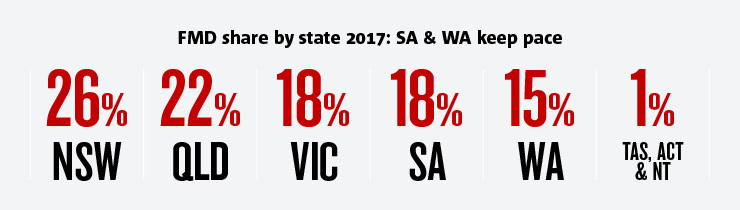

This next chart requires a little more analysis. As would be expected, the states with more farmers have more FMDs and more money deposited in those FMDs. But the FMD figures from 2014 to 2017 show that New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia were the overachievers when it came to growth in FMDs. So, while South Australia has fewer farmers than Victoria, those farmers now have almost as much saved in their FMDs as their Victorian counterparts.

Off a much smaller base, Australian Capital Territory and Northern Territory farmers have also been significantly adding to their FMDs in recent years.

Source: Department of Agriculture and Water Resources

How long until FMD deposits hit 10 billion?

Australia is certainly in a golden age of agriculture. Not only are FMDs at record levels, so too are the figures around borrowing money. This suggests farmers are confident enough to be spending on leasing or buying capital equipment. NAB’s agribusiness clients deposited over $1 billion into non-FMD accounts over the last financial year. Export earnings from farm commodities for 2017-18 are predicted to reach an unprecedented $48.7 billion.

Some of the agriculture sector’s vibrancy is down to cyclical factors such as weather conditions and a low Australian dollar. Some of it is down to structural changes such as the growth of the Chinese middle class. We’ll have to wait and see how long the boom continues.

If things continue to go well, I would expect there would be around $8 billion in FMD deposits by around 2020 and $10 billion by 2025. That will be a fantastic buffer for farmers if conditions become more challenging.