The big issue for those who don’t own a home is what happens later in life, writes Nigel Bowen.

Most of the commentary around housing affordability focuses on its immediate effects: first timers struggling to get into the property market. But the sleeper issue is what’s going to happen when generations who haven’t bought (and paid off) their house exit the workforce.

Today, most retirement standards are based on the assumption that people own their homes outright at the point of retirement. And your eligibility for the government’s aged pension does not consider the value of your home. In short, the retirement system is kind of set up for homeowners.

The problem is, for a growing number of young Australians, this is becoming a pipe dream. Among 18-to-39-year-olds, home ownership dropped to 25 per cent in 2014, down from 36 per cent in 2001, according to 2017 latest Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey.

An intractable problem

While an oversupply of apartments, interest-rate rises or a downturn may ‘correct’ high property prices in Australia’s east coast markets, experts aren’t hopeful for long-term change. Personal financial expert Noel Whittaker, and Robert Snell, director of financial advice firm, Life Values, believe the housing-affordability situation is unlikely to improve much.

“It’s not just a Sydney-Melbourne problem, it’s a nationwide crisis,” Snell argues. “An affordable house is one that’s three times the median income. If you want to buy in Adelaide you’re still looking at six times the median income for the average property.”

“Australia doesn’t have one property market, it’s got a collection of them, some of which have gone down recently,” adds Whittaker. “But, with the population expected to almost double by 2050, that’s got to keep putting upwards pressure on prices.”

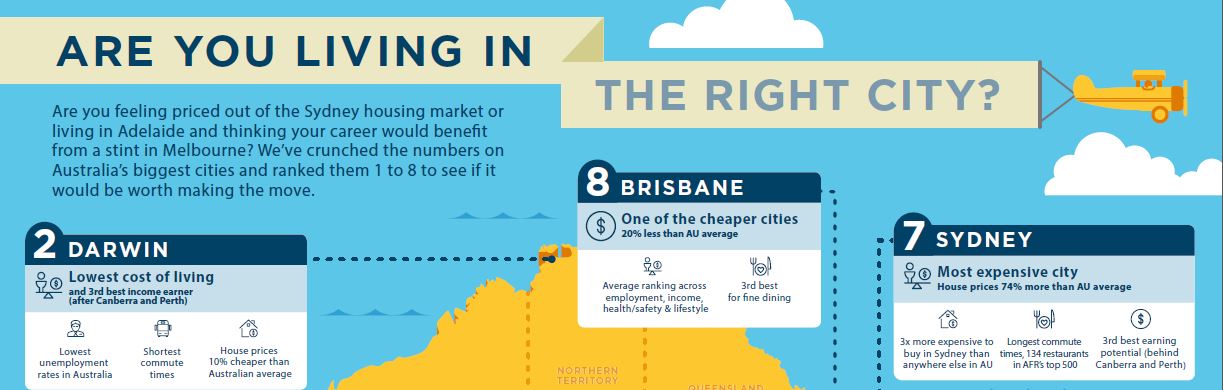

Are you living in the right city?

(Click the infographic for full view)

Accepting the new reality

“There’s a brief window of opportunity to get into the property market between finishing your education and having kids,” Snell says. “Unless you’re a high-income earner or can access the bank of mum and dad, there’s not much scope to save for a deposit while covering rent and the costs of raising children.”

“If a couple is prepared to live frugally and be single-minded about saving they can probably still scrape together a deposit. But it’s undoubtedly a lot harder than it used to be,” says Whittaker.

Would-be homebuyers may be clinging to hope, and if their focus is strong enough that may bear fruit. But they should also plan for a financially sustainable life without buying property.

For those who aren’t going to have a paid-off family home to fall back on after exiting the workforce, there are basically three options.

Financial planner Robert Snell explains some alternative options to home ownership. (2.41 mins)

Option 1: rentvesting

If you can’t buy a $2 million house in Brisbane, perhaps you can manage a $200,000 apartment in Launceston?

Snell says rentvesting – which is buying an investment property while continuing to rent – is something more Australians should consider.

“It’s not easy to explain how it works, but buying property, whether you live in it or not, allows you to build wealth quickly,” he says.

“Let’s say you saved up $10,000 and borrowed $90,000. You then bought a studio apartment in a regional town where real estate prices were rising 3 per cent a year. In 10 years, your flat will be worth $130,000. That means your $10,000 equity has increased to $40,000, assuming for the sake of simplicity you still owe $90,000. Good luck getting that kind of return on other types of investments.”

Whittaker is also a fan of rentvesting: “It’s an investment property, so you can negative gear it,” he says. “Plus, if you can arrange to live in the property for six months every six years, you don’t have to pay capital gains tax when you sell it.”

ANZ: building wealth brick by brick

Option 2: up your super contributions

“Super provides relatively safe and attractive returns, though given you can’t access your money until reaching preservation age, it’s best suited to the middle-aged,” Whittaker says.

“Let’s say you’re earning $80,000 and your employer is putting in around $8000. You can put another $17,000 in before reaching the $25,000 annual contribution cap.”

Snell likes that the returns you make on super are lightly taxed at 15 per cent.

“By upping your super contributions you’re essentially being subsidised by the government,” he says. “If your employer is putting $5000 a year into your super and you’re voluntarily contributing $20,000, around $8000 that would otherwise end up in the taxman’s hands each year is staying in your account. That money is then earning compound interest for however many decades there are until you retire.”

ANZ: maximise your superannuation potential

Option 3: build a share portfolio

“I don’t suggest people should try to pick winners, but index funds have averaged a 9 per cent return over the past 30 years,” Whittaker says.

“Unlike property, you don’t need to save $30,000 and borrow $600,000; you can invest in some index funds for as little as $500. It’s a liquid investment, so if you need $5000 to cover an unexpected medical bill, you can access some of your money. Also, given franking credits, the dividends you earn on your shares are nearly tax free.”

Snell is less enthusiastic about this option. “If you’re saving for retirement why would you want a liquid investment?” he asks. “Why buy and sell shares directly and pay capital gains tax when you could be indirectly investing in the sharemarket through increasing your super contributions and paying much less tax?”

ANZ: trade shares with confidence

Making a commitment

You can still enjoy a comfortable retirement without owning the home you live in, but to do that you have to make the same kind of sacrifices those paying off a home.

“Financial independence is achievable,” agrees Snell. “However, you’ve got to be willing to make a serious, long-term commitment to investing a substantial proportion of your income. You’ve got to make a decision. Are you going to be a property owner and go for it? Or are you going to be renter? If you’re not going to have that forced savings of a property you’ve got to get stuck in and save for your retirement.”

The sooner you make a decision and act, the more likely your plan B is going to get you to the same place as plan A.